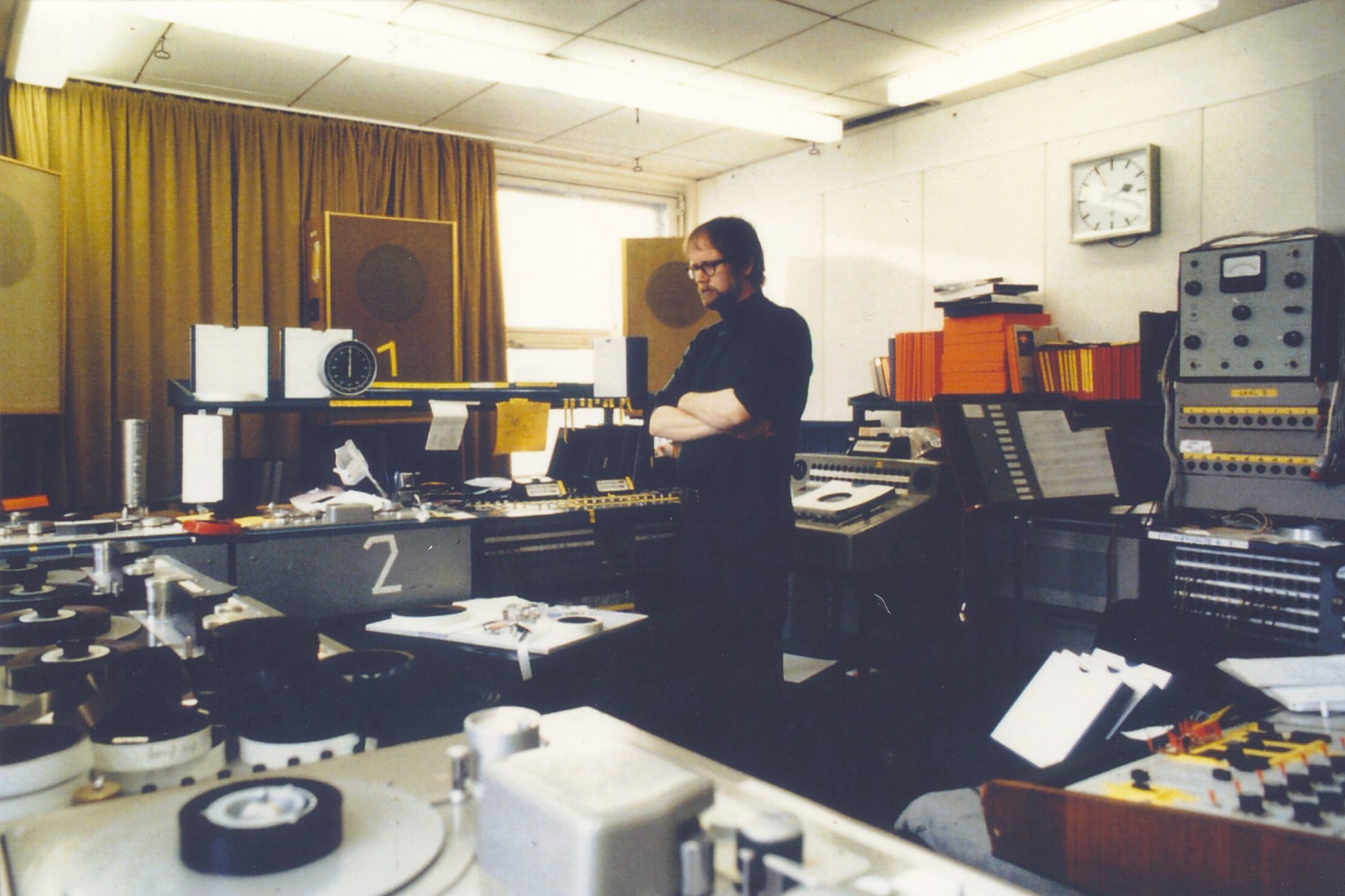

Photographs: John McGuire in the Studio for Electronic Music, West German Radio, Cologne, December, 1978 by Volker Müller

Foreward

John McGuire’s music stems from his realization that serial techniques of musical organization and minimalist aesthetics could coexist. The fruits of this cross-fertilization were not at all obvious at first, as the two camps started off in opposition to one another to a certain degree. On the one hand, serial composers often prided themselves on opaque technical maneuvers and abstract musical textures. This school of thought typically employed sequences of magnitudes to determine the properties musical objects, or the types of transformations between them. Integer series could also suggest degrees of similarity from one event (or set of events) to the another. In contrast, the first wave of minimalist composers tended to gravitate to transparent, audible processes that eschewed concealed mechanisms. Steve Reich’s Clapping Music(1972) can be performed by two amateurs with no instruments and hardly any practice.

A native of California, McGuire graduated from Occidental College in Los Angeles. In 1964 he continued his work as a graduate student at UC-Berkeley. McGuire moved to Germany in 1966 where he spent the next three years pursuing his interests in composition further. Making the most of his time, he assimilated many current trends by studying with Krzysztof Penderecki at the Folkwang-Schule, and participating in two of Karlheinz Stockhausen’s famed seminars in 1967-68 at the Darmstadt Vacation Courses for New Music. Not sure where his career would take him, McGuire returned to California in 1969, only to travel back to Germany again in 1970. He remained there until 1998, when he moved to New York City.

When McGuire entered the European scene, serial procedures were proving themselves astonishingly flexible. For example, Stockhausen’s Stimmung (1968) – a thoroughly serial piece, as Richard Toop argues – used just one dominant ninth chord throughout the entire hour-long composition. It is sung by six singers sitting around a circle, an arrangement Stockhausen might have seen during his 1967 teaching stint at UC-Davis. The idea that a single compositional technique could produce a wide variety of musical styles was an idea waiting to be explored more radically.

When he returned to Germany in 1970, McGuire studied in Utrecht with Gottfried Michael Koenig, where he had access to a small electronic studio and learned the basics of voltage control. Soon thereafter, McGuire joined a circle of Stockhausen collaborators in Cologne, including Johannes Fritsch, Rolf Gehlhaar and David Johnson. These young composers and performers formed a group called the Feedback Studio, under whose mantle they independently published essays, produced concerts and worked with the small but powerful EMS VCS-3 voltage-controlled synthesizer.

Voltage control is a technique whereby a variation in electrical voltage can trigger, organize or automate parameters of sound in a synthesizer. A sound’s pitch, volume, timbre or duration can be controlled by such a voltage curve. The concept proved to be a simple and efficient tool that still governs the operation of electronic music synthesizers today. Voltage control provided the missing piece that enabled McGuire to conceive of and produce Pulse Music I and III. At the electronic music studio at the Cologne Conservatory, McGuire created a voltage-control experiment which he later called 108 Pulses. This rather abstract title simply refers to the number of control triggers that generate a single loop of pulses. It led to the composition of Pulse Music I from 1975-76.

The term “pulse music” not only serves as a general descriptor of the sounds in the composition, but also refers to the subcutaneous voltage-controlled pulses of electricity that created them. In Pulse Music I, the “pulses” range in duration from 12 to 4 Hz. Numerical ratios not only govern the relationship of pulses within a section, but also between sections. From one section to the next, a new layer gets superimposed on top of a continuing one. This technique is akin to the one Stockhausen used in his orchestral composition Gruppen(1955-57). Within the pitch domain, McGuire cycles through the entire circle of fifths twice. This harmonic progression coyly refers both to the most common manner of creating a sense of harmonic motion in classical music – and, by closing a cyclic series of pitches – gives the impression that the piece stands still.

Commissioned retrospectively for the Pro Musica Nova festival at Radio Bremen, Pulse Music II takes somewhat pared-down concepts of musical ordering and transplants them onto an acoustic orchestra made of up pianos, strings, woodwinds and organ. The result is an organic, mesmerizing musical texture reminiscent of Debussy, but organized serially.

Pulse Music III was commissioned by and produced at the electronic studio at the West German Radio – the same place where Stockhausen composed Kontakte (1958-60) and Hymnen (1966-67). After spending nine months at home composing the piece, McGuire was able to use a now-legendary synthesizer – the EMS Synthi 100 – at the WDR studio. For seven additional months, McGuire worked with the audio engineer Volker Müller to realize the piece. It was premiered in January 1979. Several innovations allowed McGuire to develop his musical language still further. Pulses as fast as 64 Hz produce a hypnotic shimmering texture in many sections. McGuire spatialized Pulse Music III, allowing pulse streams to seem as if they move in the air around the listener. According to McGuire, Pulse Music III was his “firstattempt to find an aural analog to visual perspective”.

Indeed, McGuire’s music naturally invites comparisons to visual art. Don Flavin’s fluorescent-light installations, which McGuire saw at the Cologne Kunsthalle in 1973, inspired him to search for a way “make sounds glow”. An overlooked aspect of McGuire’s music is the way one’s impression of it – like plastic art – changes depending on where one is spatially located in relation to the sound source(s). By moving around, one can potentially hear standing waves which“seem to take the form of pillars of sound that one could almost reach out and touch, as in a dream”.

McGuire’s Pulse Music series is a poetic testament to the friendships and influences between the American West Coast and the Cologne school of German composers. It is also a joyous and optimistic record of an astonishingly fruitful use of the music technology in the 1970s, a period of intense innovation and development. The shimmering textures, calm presence and kaleidoscopic colors in McGuire’s music are reminders of a world full of joy and vibrancy.

– Paul V. Miller

John McGuire interviewed by Tim Rutherford-Johnson

Introduction

Minimalism, according to one familiar telling, was an American reaction to, push against, or swerve away from Europe’s angular, intellectual, inscrutable high modernism. It distanced itself from the schools of Darmstadt, Paris and Cologne, and emerged almost organically out of the Pacific coastlines of California and the gridded manmade cliffs of Manhattan. This is a compelling idea, and like many myths contains a lot that is true. But what if it was only part of the story? After all, La Monte Young’s earliest drone pieces were essentially twelve-tone works stretched across extremely long durations; and Belgian composer Karel Goeyvaerts was experimenting with a form of “static music” derived from serial methods as early as 1952.

John McGuire was born in California and studied first at Occidental College in Los Angeles and at the University of California, Berkeley. Between 1966 and 1968, inspired by encounters with the music of Karlheinz Stockhausen and Pierre Boulez, he travelled to Europe to study at the Darmstadt Summer School (with Stockhausen) and at the Folkwang Hochschule in Essen (with Krzysztof Penderecki); in 1970 he returned to Europe again to study computer composition with Gottfried Michael Koenig at the Institute of Sonology in Utrecht. McGuire’s experiences, and the music that he composed after this time—in particular the three Pulse Music pieces on this recording, and 108 Pulses, which immediately preceded them—is not quite a synthesis of the two supposed opposites of serialism and minimalism, but more of a realization of one through the aesthetic of the other.

Rather than tone rows or number sequences, the fundamental principle of serial technique is the idea that musical sounds may be described as combinations of distinct “parameters” such as pitch, duration, and volume: although Messiaen’s Mode de valeurs et d’intensités (1949) was not the first work of total serialism (it is not strictly serial at all; and anyway Babbitt got there first with his Three Compositions for Piano, 1947–8), the multi-dimensional musical space that Messiaen created by treating pitch, duration, volume and attack independently from each other was what attracted the postwar generation. Stockhausen and Goeyvaerts both encountered the piece at the 1951 Darmstadt courses; Stockhausen’s description of Messiaen’s piece as “fantastic music of the stars” could easily be applied to the constellations of flickering points in Pulse Music I. McGuire’s music locks serialism’s warped geometries onto an evenly spaced grid, preserving serial music’s multi-dimensionality but smoothing over its wildest disjunctures and sharpest angles. If serialism is Montreal’s Habitat 67 modular housing complex, or London’s extravagantly angular Hayward Gallery, McGuire’s pulse compositions are akin to the primary-coloured grids of Le Corbusier’s L’Habitation apartment complex—a cooler expression of similar materials and principles. As McGuire himself notes, “Pulse Music I is, structurally, a relative of Gruppen.”

Listening to McGuire’s music—especially the single, twenty-minute tableau of 108 Pulses—what is most striking is its dialogue between continuity and discreteness. Every layer of pulses is made distinct through its timbre, register, and tempo. We hear them first as a plurality rather than a unity, organised like objects on a table or stars in the sky (in the three Pulse Music pieces, every so often the sky rotates and the stars appear in a different arrangement). Yet our ear naturally starts to draw connections, and as it sweeps between one layer and another what was discrete becomes continuous. Pulses become flows; quantitative reality becomes qualitative experience.

McGuire’s early pulse pieces were composed electronically, in the newly built Studio for Electronic Music at the State University of Cologne, but Pulse Music II adapted his ideas to an orchestral canvas. McGuire wrote the piece in 1975 and 1976. A year later, it was commissioned retrospectively by the composer and radio producer Hans Otte for his Pro Musica Nova festival at Radio Bremen. Alongside the Bremen orchestra, conducted by Klaus Bernbacher, were four pianists—Christoph Delz, Herbert Henck, Deborah Richards, Doris Thomsen—and McGuire himself playing a series of twelve drone-like chords on the organ. The techniques of the electronic Pulse Music pieces required a speed and precision too great for live musicians, so for Pulse Music II McGuire adapted his method to an expanding progression of durations; this had the advantage of being much slower and requiring none of the carefully calibrated tempo changes of Pulse Music I or III. It was still based, says the composer, “on what seemed to me an interesting foray into a completely different kind of time structure. Complex time structures had, by 1975, become a condition for me in two senses: a compositional requirement and maybe an illness.” The present recording was made by Radio Bremen at the work’s first and only performance, and has been held in their archive since then.

– Tim Rutherford-Johnson

Interview

I. Darmstadt

Tim Rutherford-Johnson: Having lived and studied in California, how did you find yourself in Darmstadt in 1966?

John McGuire: Like many of my colleagues, I had been interested in new music in Europe since I first heard an LP with recordings of Boulez’s Le Marteau sans Maître and Stockhausen’s Zeitmasse. The LP was released in 1958 (Columbia Masterworks ML5275); I purchased it a couple of years after that.

My first encounter with the music on this LP was fortuitous: I happened to hear part of a lecture by a music professor at the college I was attending (Occidental), in which the professor played a recording of Zeitmasse. I had never heard anything like that before, but it did cause me to think of the introduction to the Rite of Spring—taken several steps further. I wondered: who did that? And how?

I obtained scores of the Stockhausen and Boulez pieces and began to read about new music in Europe, especially Die Reihe, in English translation. In 1964, in graduate school at UC Berkeley, I took courses in German in order to read everything I could find about the subject.

In the summer of 1965 I had the good fortune to study composition privately with Karl Kohn, a brilliant composer and pianist who was teaching at Pomona College. During my lessons he sometimes played whatever he was working on at the time, often in preparation for performances at the Monday Evening Concerts in Los Angeles. This included Stuctures II for Two Pianos and Eclát, both by Boulez, both of which he played with profound insight. These were the best “concerts” I have ever attended.

The following fall, on Kohn’s advice, I applied for and was granted a traveling scholarship from Berkeley on the basis of my plan to visit the Darmstadt Ferienkurse and possibly study in Europe, though I had few ideas about where and with whom. I had read that the International Music Institute in Darmstadt had a large collection of unpublished scores and recordings, so I arrived at the institute two weeks before the start of the courses—to read, listen, and learn about studying possibilities.

I asked one of the organizers, Wilhelm Schlüter, about studying composition in Europe. He told me that Penderecki would be guest professor of composition at the Folkwang-Schule near Essen that fall. I had been interested in Penderecki’s work for a couple of years by then (it was much discussed in the Bay Area), so off I went—from Darmstadt to the Warsaw Festival and then to the Folkwang-Schule.

How much of an influence were Stockhausen and Penderecki?

Both composers influenced me. During the years 1966–68 I studied with Penderecki at the Folkwang-Schule. I saw him twice a week for an hour. His teaching included extensive exercises in counterpoint, orchestration, composition, and free composition. He was an excellent teacher, very intuitive and very generous; talk often continued well past the hour at a local cafe.

At the same time I was busy with scores and recordings of Stockhausen. The music I was writing thus tended, student-like, to combine aspects of the work of both composers, in particular Penderecki’s technique of layering bands of sound, Stockhausen’s precise and complex timing (or what I could make of it) and the innovative notations of both composers. To give an example, I thought of an exercise in what is sometimes called “translation.”

Among the scores in my possession at the time were Stockhausen’s Zyklus for one percussionist (1959) and Penderecki’s String Quartet No. 1 (1960). Penderecki’s score was prefaced by a list of special—mostly percussive—string effects such as Bartók pizzicato, knocking on the body of the instruments as though they were drums, col legno battuto, col legno ricochet, fast bowing behind the bridge, and so on. Stockhausen’s instrumentation in Zyklus was large and varied enough to be capable of producing analogues or close approximations to all of these effects. The first part of the exercise was to assign each of Penderecki’s special effects to one of Stockhausen’s percussion instruments. The next part was to rewrite Penderecki’s score using Stockhausen’s notation.

The exercise taught me a lot about the two pieces and what might underlie both, so I felt that I had learned something valuable, and enthusiastically showed my new score to Penderecki. He was not amused. I didn’t show it to Stockhausen.

II. Utrecht

In 1970 you attended courses at the Institute of Sonology in Utrecht. What drew you there?

A need for more information about electronic music. I wanted to make a tape piece someday if I could find a studio in which to do so. The Institute of Sonology was part of the preparation.

My first encounter with electronic music was the soundtrack of the movie Forbidden Planet, from 1956. Later, in the early 1960s, came the music of Stockhausen, and in the late 1960s voltage-control patterning. I first became acquainted with the latter during the academic year 1969/70 when, back in Berkeley, I spent time with two friends, Alden Jenks and Martin Bartlett, both of whom were working with voltage control modules that they had built themselves. Alden had been inspired by David Tudor, who at the time was working on his own modules and had, for a while, lived at Alden’s house in Oakland.

In 1970 I returned to Germany. After my return I heard that Gottfried Michael Koenig, director of the Institute of Sonology, was lecturing on voltage control. Utrecht was only two hours by train.

What influence did Koenig have on your work? How did this period influence the creation of your work Frieze (1969–74)?

My first ideas for Frieze, sketched out in 1969, were for a two-piano piece in which I would try to develop evolving patterns such as I had first encountered during electronic improvising sessions around the Bay Area. I preferred not to use electronics—at least not yet—because to do so looked like it would require years in an electronic studio, which of course wasn’t going to happen. So I chose the piano as “abstract” enough for my purposes.

These improvisation sessions took place in different sorts of settings. Several were public and took place at the Palace of Fine Arts in San Francisco. One of these events featured Alden Jenks improvising with electronics while I played the French horn and a giant balloon was slowly inflated. We repeated this later (without the balloon) at Mills College. Other events were semi-public. Martin Bartlett was teaching at Pacific High School where he regularly demonstrated his newly-constructed equipment to his students and whoever else might be listening. He sometimes described the music as “steady state”; I found it extremely volatile but with its own elegance. At other times it was just Alden Jenks and me having a good time in his workshop.

I attended Koenig’s lectures at the Institute of Sonology during the winter semester of 1970. From Koenig came (at least) two things that were essential to the Frieze project: first, foundations and procedures in voltage control (with intriguing illustrations), and second, algorithmic composition. It was in Koenig’s lectures that I first encountered the term “algorithm.” I followed his lectures on the subject with interest because it seemed that algorithms might prove to be a useful tool in constructing the rhythmic/melodic patterns that were gradually coming into view.

Frieze took four years to write. There were many influences but Koenig’s systematic approaches to structure were among the most important. For example: the time structure of Frieze is generated by a rather elaborate, manually constructed algorithm that controlled various relationships between speed (the length of the shortest note in a given repeating pattern), period (the overall length of that pattern), and duration (the total length of a given set of repetitions of that pattern). I often reviewed my notes from Koenig’s lectures during the one and a half years it took to develop the structure.

How did you begin using electronics in your music?

By 1970 I had, for several years, been using ideas and techniques (such as tape montage and graphic notation) that had originated in electronic studios and applying them to instrumental music.

This approach came at least partially from my lessons with Penderecki. To give an example from one of Penderecki’s assignments: draw fifty sketches for string quartet, then assemble them into a piece. This was akin to splicing together strips of tape. So I was using techniques associated with electronic music long before I got to work in a studio. During that time I also drew a graphic score of "Gesang der Jünglinge" (from the Deutsche Grammophon LP, SLPM 138 811), some of whose notation found its way into Penderecki’s assignment.

It was still several years before I had the opportunity to work in an electronic studio. I did some work in Utrecht, but it was a in a very small “student” studio, with equipment from the 1950s, one day a week. Then came the Feedback Studio in Cologne. Its founder, the composer Johannes Fritsch, gave me a key and more or less unlimited access to the small studio that he, David Johnson, and Rolf Gehlhaar had set up in 1970, after their return from Osaka. The studio consisted of a VCS3 synthesizer, four tape recorders and a mixer. During the early 1970s I spent hundreds of hours in the studio with the synthesizer, just to learn what was possible and to work out where I would want to go if I ever got into a larger studio.

During that time (1970–75) I made translations from German to English of the realization scores of Stockhausen’s Kontakteand Telemusik. By 1975 I felt ready to try my hand at an electronic piece just as the new Studio for Electronic Music at the newly built State Conservatory in Cologne was opened. Of course I thought of working there, but I didn’t know if it would be possible. For one thing, I was not a student at the conservatory, nor did I know if I would be accepted if I were to apply. I had little idea of what equipment was going to be available.

I think it was in 1971 that Stockhausen was appointed Professor of Composition at the conservatory. He hired the English musicologist Richard Toop as his teaching assistant. Richard lived near the conservatory, where, in addition to assisting Stockhausen, he lectured in new music. His apartment became a meeting place for young composers. He had a huge collection of recordings of new music, knew everything in it and loved to talk the talk. Many of us learned from him.

In 1974, after I had finished Frieze—whose composition he had been following—I asked Richard what he thought I should do next. He suggested an electronic piece at the newly opened studio in the conservatory. I then spoke with the director of the studio, Professor Humpert, who OKed my working there as a conservatory student. My work in the conservatory studio resulted in the preliminary study 108 Pulses and in Pulse Music I, which I produced during 1975 and 1976. 108 Pulses was never performed; Pulse Music I had its premiere at the conservatory in 1977.

To what extent were you aware of East and/or West Coast minimalism at this stage?

I was not aware of that terminology until much later. In 1969 I had heard performances in the Bay Area of Violin Phase by Steve Reich, and of In C, by Terry Riley, but I didn’t associate either with something called “minimalism,” East or West Coast. I assumed that they were both Bay Area composers.

What I was aware of was mostly European. I had first encountered something like “minimalism” in the Polish composers whose work I had first heard in the mid-1960s while at UC Berkeley. I was especially interested in the works of Henryk Górecki, whose Elementi and Choros, recordings of which circulated among composers in the Bay Area, had left a deep and lasting impression. I ordered the scores from Warsaw. In retrospect, one aspect that I found so impressive was Górecki’s practice of composing in opposing static layers whose very opposition seemed at times to overwhelm the stasis and trigger series of changes that then constituted a form.

In 1966 I attended the Warsaw Autumn. The festival featured an exhibition of new scores by Polish composers. One of the scores I happened upon while browsing around was the Third Piano Sonata of the young composer Krzysztof Meyer. Meyer had taken the step of substituting the sound bands (usually of clusters) that were popular in Poland at the time for bands of repeating patterns—like slowed-down wave forms—while preserving the “band composition” premise. The result was a piano music based on repeating patterns that had nothing to do with traditional functions of ostinati (preparation, accompaniment, dissolution, etc.) but are displayed for their own sake.

Important in this context was the book Nonfigurative Music by the Swedish composer Jan Mortensen. Mortensen analyzes musical phenomena like those described above in his own works and in those of Ligeti, Penderecki, Górecki, and Cerha. I found the book to be of great interest. I loaned it to Penderecki ...

The most spectacular example of “minimalism” that I encountered during those years was a 1968 performance in Cologne of Stockhausen’s Stimmung. I had acquired a score of the piece, which contained a large number of different rhythmic patterns in a variety of tempi, and—something really new to me—intersecting overtone waves: using changing vowels to sweep up and down overtone series like the analog filters which Stockhausen had used to such great effect in his electronic music. The architecture of the piece—essentially the same in both rhythmic and pitch domains—generated these intersecting waves among the six singers. The effect was often magical; Stockhausen’s technical virtuosity was, as usual, astonishing.

III. Cologne

I’m fascinated by the Feedback Studio, which I believe is an under-acknowledged influence in European music in the 1970s. How did you become involved with it? Were you ever an “official” member of the group?

I had known Johannes Fritsch, Rolf Gehlhaar, and David Johnson for several years prior to the founding of the Studio. They had all worked for Stockhausen since the mid-1960s. Fritsch was a violist in Stockhausen’s ensemble. Gehlhaar, who I had known at UC Berkeley, had moved to Germany in 1967 as Stockhausen’s personal assistant. David Johnson had worked as an audio engineer assisting in the realization of Stockhausen’s Hymnen.

The concept of the Feedback Studio included a variety of functions: publishing the scores of its member composers, instrumental and electronic music productions for stage and radio, a journal (Feedback Papers), monthly concerts and presentations at the studio itself (I gave talks about my pieces Decay, Frieze and Pulse Music I), and concert tours by the three founders in which Fritsch played viola, Johnson played flute and ran the electronics, and Gehlhaar played an amplified, deep bass instrument that he had invented, built, and named “Superstring.”

Soon after the three had decided to form the studio they asked composers they knew to join them. At first these were me, Peter Eötvös, Michael von Biel, and Mesías Maiguashca. All of these composers had worked for or with Stockhausen in some capacity. All of them lived in Cologne. Four of the six (excepting me and von Biel) had been with Stockhausen in Osaka: Fritsch as violist, Johnson as flutist and technician, Gehlhaar as organizer and tam-tam player, and Eötvös as pianist and conductor.

I was a member of the group insofar as it can be called a group. It was really a bunch of composers who wished to collaborate with colleagues to publish their own work (Autorenverlag) and thereby avoid the pitfalls of “official” publication. This association gave me the priceless opportunity to get to know a studio—albeit a small, modest one—very intimately. My gratitude persists to this day.

How did your work progress from Frieze to 108 Pulses to Pulse Music I?

After finishing Frieze in 1974 I felt the need for some time off from composing, so I turned to my piano and began improvising for a few hours each day. I had a vague curiosity about where this might go and planned to let whatever seemed to want to happen, happen. After the first few days of improvising, I noticed that I had an unconscious tendency to search, by trial and error, for rhythmic/melodic patterns lasting for a few seconds and displaying time relations of 3:2 or 3:4 though I had started with no such plans or intentions.

After having found a more or less usable pattern while improvising I would repeat it over and over again until it was memorized, then write it down. In this way I collected maybe one hundred keyboard patterns in about three months (the book is lost).

Besides the improvisations, during that summer of 1974 I was often at the Feedback Studio, still playing with the VCS3. As these visits continued I began to tire of the complex sounds and events that seemed to be an innate tendency of the VCS3 and of analog synthesizers in general. I wanted to find something that held my interest in the way that the piano improvisations were doing. In both cases I was looking more or less consciously for something with which to “clean my ears”—to find a point zero.

Drawing on my experience with Kontakte and on my improvisations, I recorded a number of sine tones—D and G in various octaves—cut all the recordings to three-inch sections, and spliced them together to form a loop of several seconds’ duration. At a playback rate of 38 centimeters per second this gave each tone slightly less than 1/13 of a second. I then ran the loop through two tape recorders. At that speed and density the resulting sounds seemed to literally occupy the air and render it crystalline. I decided to pursue this further in the electronic studio at the conservatory, starting in 1975.

That fall I brought one of my piano improvisations to the studio with the idea of turning it into a quadraphonic loop using only sine tones. This was to be a preliminary study in preparation for the larger project, which eventually became Pulse Music I. I called it 108 Pulses after the number of control, or trigger, pulses governing the loop.

The first problem with this procedure was the 16-track tape recorder. Only gradually did I begin to grasp what the availability of all those tracks implied: a multi-layered music, such as I had been picturing for years, but with limitless possibilities of synchronization.

The question became: what layers? This question forced me to look for a new method of synchronization for multiple, coordinated layers. This in turn would influence the answer to “what layers?” in the same way that any instrument influences what is or can be written for it.

After a number of failed experiments the audio engineer I was working with, Marcel Schmidt, came up with the idea of recording a click, or “trigger” track at a given speed (in the case of Pulse Music I in the range of about 4 to 12Hz), on one of the sixteen tracks, routing that track to a sequencer (ARP 2500) and from there back onto the tape recorder where anything coming from the sequencer (in this case sine tones) would be automatically synchronized with the click track. For example, one layer might have an event every twelve clicks, or pulses, another every eighteen pulses, and another every three pulses. All layers would be synchronized with the single click track and thus with one another. Without this device neither piece could have been realized.

This and other problems—such as the location and motion of the sounds in quadraphonic space—had to be solved before it would be possible to do what I wanted to do as, along the way, I figured out what it was that I wanted to do.

What other influences were you absorbing at this time? I believe some visual artists were important too? Anyone in particular, and in what ways?

There were many musical influences, of which I will mention only a few.

I heard more from Steve Reich, who visited Cologne with his ensemble in 1973, and from Terry Riley in several performances in Cologne and Bonn.

Walter König’s bookstore in Cologne had an LP of La Monte Young which turned out to be of great interest. One side of the LP was a drone that, under the right circumstances, generated very strong standing waves. I had an unheated room whose temperature seemed especially suited to the production of these phenomena; I sometimes played the LP while walking among the waves, which seemed to take the form of pillars of sound that one could almost reach out and touch, as in a dream. It was a revelation.

I often played pieces from A Collection of Highland Pipe Music, compiled by Angus McKay and first published in 1825, on the piano. I had found the book in the UCLA music library during a visit to California, and made photocopies. What caught my attention was page after page of repeating rhythmic/melodic patterns in which one or two notes of the pattern were altered in each iteration. I had never before encountered a music in which the static and the moving elements were on such obvious display but in such exquisite balance that, even playing the pieces on the piano, they were mesmerizing. I adapted the technique to the repeating patterns in Frieze, where it appears on nearly every page.

Another piece of the puzzle was Boulez’s system of harmonic multiplication. In 1965, during our weekly meetings, Karl Kohn had tipped me off to its use in Structures II for Two Pianos. I found detailed information in an article by Josef Haüsler, which had been published by Wergo with the Kontarsky recording of the piece. I adapted the technique to the harmonic grids of Frieze; this became an essential step in outlining the harmonic and melodic moves. (I described the procedure in Feedback Papers 11, November 1976—the periodical published by Feedback Studio, now out of print.)

There was some literature, in particular regarding cyclic structures, their mythologies and meanings, in W.B. Yeats, A Vision and Clive Hart, Structure and Motif in Finnegans Wake.

The visual artists who had most captured my attention at the time were Agnes Martin and Dan Flavin—although it is difficult for me to say in what ways I was or wasn’t “influenced”. It was, again, just a feeling—perhaps of awakening to a world of which I had previously been unaware—that seemed to suggest a gateway to a sacred space which only existed by virtue of their surface quiet. My interest in Flavin became especially strong when I was doing Pulse Music III. I wanted to make something that sounded like what a large Flavin installation at the Cologne Kunsthalle looked like.

In this spirit Pulse Music I and III were both originally conceived as sound installations—as very large loops (about 20–25 minutes) to be played continuously. This didn’t happen at the time because a 25-minute tape loop was a practical impossibility. Much later, in 2012, with a totally different technology, Pulse Music III was presented as a quadraphonic loop by the Cologne group reiheM.

The apparent paradox involved was the fact that for the most part these pieces would, for practical reasons, be presented in concerts where they would be played once, while at the same time I thought of them as endless loops. So they had to be both infinite (played over and over again) and finite (played once).

Can you expand on how Dan Flavin’s work influenced or inspired Pulse Music III?

The installation at the Cologne Kunsthalle [Dan Flavin: Three Installations in Flourescent Light, 1973] was set up in a large, rectangular room with all four walls lit by patterns composed from hundreds of fluorescent tubes of different colors. Standing in the center of all this, my first impression was of an especially vivid study in perspective. I got lost in the implied distances. Part of this impression was due to the fact that the walls were aglow with the light of many colors that blended in ways that varied with the light’s position in perspective – the further distant, the more mixed, the more hazy, the light.

So there were two aspects to what this installation “looked like” to me: glowing geometric patterns bound to an experience of perspective that was greatly enhanced by the light. My reaction was to start looking for ways to make sounds “glow.” After much trial and error I decided on the following: given that the new synthesizer at the WDR—an EMS Synthi 100—had six voltage-controlled sine-tone oscillators the sounds are composites of six sine tones: a fundamental and five partials tuned in whole number relationships, for example 1-3-4-6-9-18. The fundamental (1) is very soft; the partials increase in loudness from lowest to highest (18). In addition, each of these sine tones has a different onset transient, increasingly hard, or sudden, toward the top. This particular relation of loudness to onset transients seemed to lend the sounds at least some of the imagined glow.

I should emphasize that there was very little theory behind any of this, just a lot of experimentation, every day over a period of weeks—the “Experimentierphase,” as the indispensable audio engineer, Volker Müller, called it. In all, the piece required seven months of daily work in the studio, much of which was taken up with intonation and onset transients, particularly at high speeds where onset transients can quickly get noisy.

Pulse Music III was my first attempt to find an aural analogue to visual perspective. This was done by cross-fading pulse series from front to rear of the aural space in continuous spatial loops. That is half of the aural image. The other half circled the space from left to right, providing (or so I hoped) a contrasting comparison to the front-rear motion. The front-to-rear pulse series was made of the aforementioned “glowing” pulse sounds and was easy to follow. Despite this I felt that the image was only partially successful; our ears are set up to track left-right motion much more easily than front-rear, so that the balance between the two directions was skewed.

IV. Serialism and Minimalism

Much has been made of the way in which your music synthesizes the aesthetics and techniques of minimalism and serialism. Is this something you have set out to do? What do the two terms mean to you?

Given my dual background an attempt at such a synthesis was probably inevitable—a means of maintaining sanity. But it had always been a predilection of mine, when confronted with disparate, apparently contradictory phenomena, to look for a synthesis (see the example of Stockhausen’s Zyklus and Penderecki’s String Quartet No. 1, above). The attempt at a synthesis of minimalism and serialism is just a later manifestation of a tendency that had been there as long as I can remember.

My acquaintance with what became known as “minimalism” began at the central public library in my home town of Long Beach, California, when I was about 17. The library owned a very large collection of scores and recordings of Henry Cowell. I found much of the collection riveting, and Cowell’s book New Musical Resources essential. I was especially drawn to a percussion piece called Ostinato Pianissimo. I had never seen anything like it before: several ostinati taking place simultaneously at different speeds. The idea seemed to be that a clear perception of multiple “times” would require that these times be embodied by periodically repeating patterns, as is the case in the domain of pitch. I had no particular use for this information (I wasn’t composing yet), but it emerged about ten years later as key.

It was this understanding that led me, around 1970, to a study of Stockhausen’s serialism, especially as practiced in Gruppenand Stimmung. I once asked Stockhausen if he would agree that, given the periodic substructure of Gruppen, the removal of the surface rhythmic complexity would leave a complex example of “minimal music”, that is, multiple periodicities. He sort of agreed.

So I can’t be credited with this synthesis. Perhaps I’ve made some contribution toward what could be considered a group effort that includes many kinds of contribution, but whatever that group effort aims at remains, to me, a mystery.

In what way might this be reflected in the Pulse Music series?

For example: Pulse Music I is, structurally, a relative of Gruppen. It has twelve different tempi, related chromatically, as does Stockhausen’s piece. Unlike Gruppen, the tempi are arranged as a one-interval series of twelve frequencies in the pulse domain (below 16Hz) that are introduced one-at-a-time, in sequence. These govern the sections of the piece.

Pulse Music I consists of twenty-four sections, each with its own tempo, with each tempo generated by two “subtempi” in the proportions of 3:2, 3:4, 3:8 and 3:16. The same proportions determine the twenty-four changes of tempo. For this reason the sections are characterized by temporal ambiguity. This ambiguity resolves every minute or so at points of coincidence, where a new relation begins. The whole is completely cyclic, moving a step at a time twice through the circle of fifths in the domain of pulse. It does the same thing, in parallel, in the domain of pitch (above 16Hz). In other words, the same information governs both domains.

The idea was to generate static, multilayered aural images whose changes of speed and tempo would grow out of their structure and therefore, though lacking any sort of narrative, feel organic and inevitable.

The time structure of Pulse Music I. Each of the 24 sections has its own trigger pulse speed, here given in hertz (pulses per second) from 12.34 (section 2) to 3.46 (section 24). The dual periodicities and durations are derived from this sequence of speeds. The diagram shows about 10 octaves, or frequency relations of 1:2, from 12Hz to 422/3 seconds.

Finally, is there a progression or development of technique between the three Pulse Music pieces?

When I went to the WDR for the first time, in 1978, I was still exploring the possibilities opened up by the “instrument” that I had first used in the conservatory studio three years previously. It did not require a lot of equipment and the equipment that was required, with the exception of multi-track tape recorders, was available in most studios at the time: a number of voltage-controlled sine-tone oscillators, a sequencer large enough to accommodate whatever patterns were envisaged and a 16-track, or at least two

8-track tape recorders.

With my “instrument” reconstituted at the WDR I could focus on expanding its possibilities. Among the things I wanted to try out in the new piece were:

- Speed increase: the fastest click speed of Pulse Music I is 12Hz, in Pulse Music III this increases to 64Hz, which, depending on the material activated, can result in a shimmering blur.

- Continuous spatial loops in both left-right and front rear configurations.

- Continuous motion in space via programmed cross-fading of layers.

- Overtone sets with “inverted” envelopes, that is, loudness increases from fundamental to highest partial.

Pulse Music II is for acoustic instruments—four pianos, strings, woodwinds, and organ—and explores a different kind of time structure that also had at its core a system in which durations are defined by a pair of component periodicities, and vice-versa. The difference is the absence of the implication of tempo change. The time structure of Pulse Music II consists of a progression of seven durations that expand in parallel to the expansion of their component periods.

In 1988, ten years after the premiere of Pulse Music II I again had the opportunity to work in the WDR studio. This project turned into a kind of “sequel,” in which the proportional series of Pulse Music II was used to coordinate waves of acceleration/deceleration in a further attempt to develop aural analogies to visual perspective. The title of the resulting piece, Vanishing Points, alludes to the subject.